New copies are currently unavailable.

You can find used copies here.

Bulk orders: send me an email..

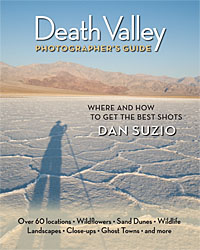

ISBN 978-0984641505

7" x 9"

114 pages

102 color photographs

5 maps

Over 60 locations

$17.95

| Newsletter signup |

Gold Award

Best Photo Travel Guide

Writer of the Year

Best Travel Guide

Interview with Dan Suzio

Author/Photographer

Why Death Valley?

I get asked that question a lot, probably because it's not exactly a friendly name. Why would anyone want to go to a place called Death Valley? I admit, it can be a harsh place, and at the same time it's the most stunningly beautiful place I've ever seen. I could describe the colors of the landscape, or I could talk about the tenacity of life - plant, animal, and human - in an environment that's not always easy to live in. But in a way it's like trying to explain why you fell in love with a particular person. I fell in love with Death Valley on my first visit in 1974, and have been back almost every year since then. There may be other places that are just as beautiful or interesting, but they don't affect me the same way.

Do you have a favorite time of year there?

I usually go in spring, partly for the wildflowers and also because that's when the wildlife is most active. But every season has its charms. The wildflower bloom starts as early as January, and might continue into June at the highest elevations. Summer and fall are good for hiking to the higher peaks. Winter is good for landscape photography because of the low angle of the sun.

Everybody thinks of Death Valley as being unbearably hot, and it is if you're on the valley floor in summer. But there's such a range of elevations, from below sea level to over 11,000 feet, that you can usually find a comfortable location at any time of year.

What kind of wildlife do you see there?

Death Valley has a surprising variety of wildlife - but if your definition of wildlife is limited to big mammals, you'll be disappointed. Lizards are the most obvious and abundant animals, with about 18 different species in the park. Jackrabbits and cottontails are common, and you'll often see coyotes along the roads. Something like 300 species of birds have been seen there, most of them seasonal. A lot of the animals are nocturnal - kangaroo rats, foxes, and most of the snakes, for example. There are also bighorn sheep, a few deer, and even mountain lions, but they're not often seen, even if you know where to look for them.

Have you seen and photographed all of these animals?

I wish! I've photographed most of the reptiles, some of the birds, lots of coyotes and rabbits, and one bobcat. The closest I've come to seeing a mountain lion in Death Valley was a couple footprints in dried mud.

Why did you write this book?

In 2009 the editor of Reptiles and Amphibians magazine asked me to write an article on photographing Death Valley, something that would be useful for first-time visitors to the park who might need some advice on where to go and what to look for. I liked the result, and for the next year or so I kept thinking about expanding it into a guidebook for photographers. Finally I told myself to quit thinking and just start writing!

What do you hope people find in the book?

My goal was to write a book that I would want to buy for myself, that includes all the information photographers need to go to Death Valley and make the most of their time there. I hope it inspires people to be better photographers, not just in Death Valley but wherever they happen to be. And for people who aren't familiar with Death Valley, I hope they learn what a beautiful, awe-inspiring place it is.

What specific advice do you give?

After a general introduction to Death Valley, I describe how I approach various subjects - landscapes, wildflowers, ghost towns, and wildlife - with advice on photographing the specific situations you'll find. For example, how to convey the sense of heat and isolation you feel on the salt flats, or how to make a good portrait of a lizard.

Part two lists 62 specific locations in and around the park, with practical information about each one - what you'll see and how to get there, along with the elevation and wildflower season - and, especially important for photographers, what time of day has the best light.

For each of the photos in the book, I include information about the camera, lens, exposure, and anything else that might be helpful in understanding how it was made. At the same time, I don't tell you how to use your camera, and I assume you have your own creative ideas for photographs.

How do you make a good portrait of a lizard? What makes a good wildlife photograph in general?

For me, it's an emotional connection with the subject, and that almost always means the eyes are the most important element. In the book, I tell photographers to shoot from the subject's eye level, make eye contact, keep the eye sharp, and make sure the animal is facing toward the light. If you can do that, you're off to a good start. And of course, composition, exposure, and lighting are just as important in wildlife photography as with any other subject matter.

When you decided to write the book, did you go to Death Valley specifically to research it? Or did you write it from memory?

A little of both. I started by reviewing photos, notes, and maps from previous trips. Then when I felt I had a pretty good draft, I made a couple more trips for fact-checking and additional photography.

Who's the publisher?

That's a long story! After a lot of research into the various publishing options, and a lot of number-crunching, my wife and I decided I should publish the book myself. So after the writing was done I jumped right into the publishing business. It's been a huge learning experience - there are a lot of things I would do differently next time - but overall I think it was a good decision. One unexpected challenge was finding a company name that we liked, that wasn't already taken. We finally settled on Nolina Press, after one of my favorite desert plants.

What's your background in photography?

I can't remember not being interested in photography. I got my first camera when I was about 14 years old, and photography has been an important part of my life since then. Around 1978 I started licensing my work to magazines and book publishers. Since then my photos have been seen in hundreds of publications, several nature museums, and starting next year they'll be on a total of eight wayside exhibits in Death Valley.

Do you have a favorite photograph?

If I had to choose one favorite photo, I'd probably give a different answer every day. So I guess the answer is no, I don't have a favorite.

Do you shoot film or digital?

I shot film for decades, then switched to digital in 2005 and have never even thought about going back. I'm making better photos now than I ever could with film. For the first year or two I felt like I was learning photography all over again, and I often wasn't happy with what I shot. But the good news is that I can go back and reprocess those photos and improve them. I still have file cabinets filled with thousands of color slides, and some of them are still published regularly, but I make digital scans whenever I need to make a print or submit something to a publisher.

What else have you written?

I'm mainly a photographer - in fact, I'm still getting used to calling myself a writer. Before this book, most of my writing has just been very brief articles or essays to accompany a photo or group of photos. I blog sporadically.

For permission to publish all or part of this interview, contact the author.